One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

— W.E.B. Du Bois

I’ll never know what it means to live 24/7/365 within a black or brown skin, seeing a fight-or-flight response from those I encounter in my country’s dominant white culture. My white skin gives me the privilege of being free from that. I may not always get a fair hearing from the cop who stops me for going three miles an hour through a stop sign, but I don’t have the added expectation of being seen as fundamentally “other.” I don’t fear a beating or worse when I J-walk, and that is a privilege people of color don’t have. If I ever forget it, I need only listen to the song at the end of this column.

My blog post four days ago, My Faith’s Crisis, My Faith Crisis, awakened much pain and anger in people of color and evoked both harsh and gentle criticism from white anti-racists in my religion, Unitarian Universalism. Some comments were supportive, but for the most part I was called a racist blind to my role in the system of oppression that dominates the culture of the United States and of Unitarian Universalism. The criticism, and the column, went viral. As I write this, about 3,000 people have read it. That’s 2,900 more than I would expect, even on a good day.

I didn’t intend the post four days ago to be about race, but about a process in UUism. I kept it brief, which led me use words some saw as racially demeaning “dog whistles.” I had intended to follow up with a post about white privilege, but now I’m expanding it into a sort of racial/ethnic autobiography. In full disclosure, I’m considering running for the Unitarian Universalist Association Board of Trustees in 2018 and want to be as honest as I can about who I am, at least now from a racial and ethnic perspective.

When I was born in 1946 in a Jewish immigrant household in a Jewish immigrant neighborhood of Philadelphia row houses, the world was learning about the holocaust. The United States and its allies, who had liberated the concentration camps, were now resisting allowing the “displaced persons” into their countries. General George S. Patton, overseeing operations for the U.S., said some officials “…believe that the displaced person is a human being, which he is not, and this applies particularly to the Jews who are lower than animals.”

Before the war, my father and my maternal grandparents had emigrated from the same swampy village in what is now Belarus. My father left behind a brother and sister, who each married and had children. So my two uncles, two aunts and five first cousins were executed, some shot to death in 1942 and some shipped by cattle-car to Auschwitz-Birkenau when the gas chambers were ready for them in 1943. I know this much detail only because one relative, young enough to work, survived several concentration camps and death marches and wrote the history so that people like me could learn about what happened to our relatives.

The many questions I’d like to ask my father (far left in the photo above this post) remain unanswered because his health deteriorated as I was growing up, and he died when I was 11. He did convey some attitudes, though, for which I’m eternally grateful:

- I never heard him express anger toward the Poles and Russians who successively occupied his land before he fled. I never even heard him express anger toward the Germans even though their troops had murdered his siblings, nieces and nephews.

- He never tried to shield me from the uglier parts of life in Philadelphia. When I was just 5 or so, he took me with him to a police station to visit his employee, a black alcoholic truck driver who was incarcerated. and then later took me with him to pay our respects to the driver’s wife and children after the he had died in his jail cell. Whether he died from the DT’s, suicide, or a beating I’ll never know.

- He seemed to have little interest in the Jewish religion or in the state of Israel.

So where this left me was as a crusader not for Jews, or for African-Americans, or for any one group, but for whoever is being oppressed. Whoever is the least of these, to borrow a phrase from the New Testament. The serial number I’ve had tattooed on my arm is a statement of solidarity not just with concentration camp victims but with all refugees, immigrants and victims of genocide.

Around the time I graduated high school and started attending Temple University, I met a woman named Alice Johnson McDonnell. I like to describe her as a black woman who wore her hair natural before the word “Afro” was invented. She had always wanted a younger brother, and for reasons I’ll never understand, her little brother became me, this well-meaning but naive white Jewish kid. She was my mentor. I learned much about the black world from her, but she became one of those little-known civil rights martyrs — stabbed to death on a Trenton street corner as she was attempting to work with inmates of the New Jersey state prison there.

Around the time I graduated high school and started attending Temple University, I met a woman named Alice Johnson McDonnell. I like to describe her as a black woman who wore her hair natural before the word “Afro” was invented. She had always wanted a younger brother, and for reasons I’ll never understand, her little brother became me, this well-meaning but naive white Jewish kid. She was my mentor. I learned much about the black world from her, but she became one of those little-known civil rights martyrs — stabbed to death on a Trenton street corner as she was attempting to work with inmates of the New Jersey state prison there.

I also learned much doing community organization in the North Philadelphia ghetto in the mid-1960’s. At the time, young white men driving alone, or with a black woman, in North Philadelphia temporarily lost their white privilege. I’ll skip the details here and go on to a happier memory from that time.

I worked with black Temple students to organize a march in solidarity with the final Selma-to-Montgomery march. Since I was the one of us with a car, I got to be the “sound truck.” I rode along with the marchers from Temple’s campus urging local residents to join us, and many did. Later, when we reached Independence Mall, my beat-up 1956 Chevy became the speakers’ platform. The speeches were made from my car’s roof as I sat inside and adjusted the sound.

So, yes, I know about my white privilege and about systems of oppression, but where I veer a bit from what seems to be the current UU anti-racism orthodoxy is that we all do worse because of racism and the other ism’s. The world is broken for all of us. We white folks generally speaking have advantages over people of color, but we would all have it better if the ism’s could be overcome. So white people deserve to be part of the conversation. I often hear that it’s not our place to quibble over a word choice in a statement or, in my case, whether to wait 10 weeks for a new president to take office before hammering out a new plan to correct racial injustices. I know that process has been approved. I’m not trying to reverse it, but I am saying we need to hear each other better and collaborate better if we are going to build a multi-racial faith.

And don’t forget that farmer who said only “maybe” to good news and bad news. Not everything is the blessing it appears to be.

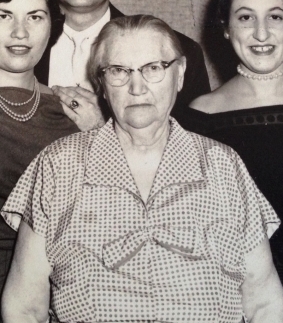

My cousin Barry had a lot of white privilege. He was a handsome, kind and poised child, and we were close. But paranoid schizophrenia became apparent in him when he was around 20. It became so bad that he would have been unable to function outside of an institution were it not for the good psychiatric care and medication his white privilege entitled him to. And without his white privilege, he might have had more trouble walking into a gun shop and legally buying a gun, which he then used to kill his parents, my uncle and aunt — the tall man at the center of the photo that heads this post and the brunette woman with glasses to his right. Barry later hanged himself in his jail cell.

And there’s my son Thomas, who wrote this after the bloody arrest of University of Virginia student student Martese Johnson . Were it not for his white privilege, he might have been hesitant to bar-hop all day and skateboard home at 2 a.m. It was not a bullet from a cop’s gun that killed him at the age of 29 but a fall from the skateboard.

As the Buddha says, we all suffer. We all have pain, which comes in many forms and from many directions.

Racism is real. White privilege is real. Systematic white supremacy is real. But until we can all share our pain and our suffering and our imperfection with each other in compassionate and mindful ways, we are doomed to staying where we are.

— Mel Pine (Urgyen Jigme)

Copyright 2017 © Mel Harkrader Pine

very touching, deep introspection!

but i wonder how to be relieved of this white privilege, is that an option?

i believe this is a land of laws

which grants rights of life, liberty & the pursuit of happiness;

laws that grant social and civil rights without discrimination.

so is it a privilege to not not one’s rights violated?

this term seems to suggest that those who are victims of discrimination and abused rights

are somehow the “norm” and one must be privileged to be free of such suffering.

certainly, racism, sexism and all forms of hate and ignorance are real as you effectively point out.

i do not wish to live in a society without laws of basic human rights. perhaps there’s a more appropriate

language which can help relieve the scourge of hatred and promote justice, imho 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

If it were possible to write a law that might help, it would create systems in which people of different categories had to meet and interact with each other.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I’ve struggled, and at times given up, trying to explain privilege can be isolating and painful as well. We need to own that hurt to know why unjust systems of society, or what Christian theologians call Social Sin, a just world is a better one even for those who benefit from the current injustice. Then we can begin to work together in love.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve struggled, and at times given up, trying to explain privilege can be isolating and painful as well. We need to own that hurt to know why unjust systems of society, or what Christian theologians call Social Sin, hurt us and a just world is a better one even for those who benefit from the current injustice. Then we can begin to work together in love.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aloha Mel,

Thanks for sharing so much about your life and history. I am deeply enriched by your family history.

I am glad that your original post got a discussion going. I am, however, sorry to see that so many of the comments are negative and reactionary, which I suspect is painful to read.

Once again, I want to express my respect for your willingness to step into the fray and participate constructively in the process.

Namo Amida Bu!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you, Ananda. My years of Buddhist practice have helped me maintain my equanimity through all if this. I didn’t want this piece to be incendiary, so I didn’t include mention of the worst personal attacks. But the reaction so far to this post has been quite positive.

LikeLiked by 2 people

When I read “My Faith’s Crisis, My Faith Crisis,” I did worry that you might be perceived, as a white person declaring his intention to run for the UUA Board of Trustees, as possibly worsening the problem rather than ameliorating it. This post tries to lessen those fears, I think. And again, I wish you luck in the most heartfelt way.

LikeLiked by 3 people